5 Lessons to Decrease Risk

Systems Design for Risk Management and Variability Reduction

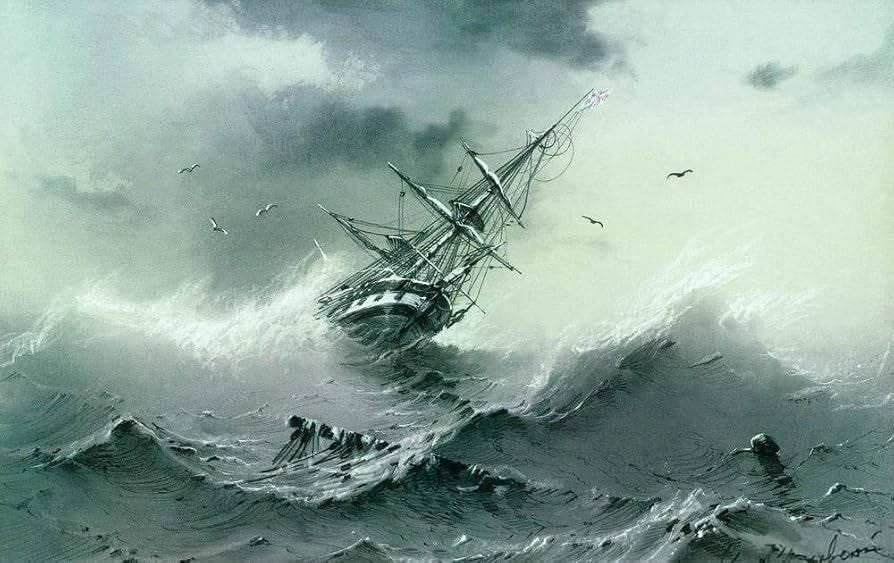

Most systems don’t fail because something extraordinary happens. They fail because something ordinary happens slightly out of sequence, slightly larger than expected, or slightly slower than planned. When we design around averages, we build systems that look efficient on paper but struggle in real life. Here are five ways variability quietly turns well designed systems into fragile ones.

1. Averages Create a False Sense of Safety

Designing for the average demand, average cycle time, or average arrival rate assumes the average actually shows up. It rarely does. Most days are above or below it. Systems built for the mean are overbuilt during slow periods and overwhelmed during spikes. The risk is not the peak itself but the repeated mismatch between what the system expects and what reality delivers.

2. High Utilization Makes Variability Explosive

As utilization increases, delay grows nonlinearly. At moderate utilization, systems absorb variation with little disruption. Near capacity, even small fluctuations cause queues to grow rapidly. Emergency departments, factories, and software platforms all exhibit this behavior. Running near full utilization maximizes efficiency only under ideal conditions and guarantees instability under normal ones.

3. One Slow Event Can Stall Everything

When fast processes depend on slow ones, variability propagates. A single delayed patient, machine, or API call creates a convoy of waiting work behind it. The problem is not the outlier itself but how tightly coupled the system is. Variability does not stay local. It travels.

4. Systems Often Create Their Own Instability

Attempts to manage variation frequently make it worse. Reacting to normal fluctuation by adjusting staffing, inventory, or production rates injects new variation into an otherwise stable process. Deming warned against this for a reason. Overcontrol creates oscillation, not stability.

5. Buffers Are Risk Management, Not Waste

Extra capacity, time, or inventory looks inefficient when measured during calm periods. But those buffers are what prevent collapse when variability appears. They are an insurance policy against known uncertainty. Removing them improves short term metrics while increasing long term risk.

Design for Reality, Not the Spreadsheet

Variability is not a rare exception. It is the defining feature of real systems. Designing for averages while hoping variation behaves is a choice to accept recurring failure. Robust systems are not those that run perfectly under ideal conditions, but those that remain functional when conditions are imperfect. The question is not whether variability will show up. The question is whether your system is built to absorb it or be undone by it.